Lab01: Adding Vector

This is a simple experiment to just get a feel of the abstraction PyTorch provides, and all the internal complexity hidden below. We will also compare the performance of basic vector addition between PyTorch, Triton, and CUDA.

Note: This experiment was done in NVIDIA RTX 3050ti laptop GPU

Vector Addition in PyTorch

import torch

size = 128 * 128

a = torch.randn(size, device='cuda')

b = torch.randn(size, device='cuda')

output = torch.empty_like(a)

output = a + b

print("PyTorch output:")

print(output)

empty_like(a)creates the same size, dtype, and device(‘cuda’) as the input tensora. It does not initialize the memory into something else, but use the garbage value of it so it’s a bit faster than usingtorch.zeros()ortorch.ones().

The exact operation of vector addition is hidden in operator+in PyTorch.

Vector Addition in Triton

Triton is an open source library ran by OpenAI, which aims to be easier to code than CUDA (fewer knobs to control, don’t need to know as deep as CUDA) but doesn’t lose the performance. Check out more information via here.

import torch

import triton

import triton.language as tl

@triton.jit # tells us this code will be compiled

def add_kernel(

x_ptr, # Pointer to the first input vector.

y_ptr, # Pointer to the second input vector.

output_ptr, # Pointer to output vector.

n_elements, # Size of the vector.

BLOCK_SIZE: tl.constexpr, # Number of elements each program should process.

):

pid = tl.program_id(axis=0)

block_start = pid * BLOCK_SIZE

offsets = block_start + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE)

mask = offsets < n_elements

# loads x and y from GPU RAM

x = tl.load(x_ptr + offsets, mask=mask)

y = tl.load(y_ptr + offsets, mask=mask)

output = x + y

# after calculation, put output back to main memory

tl.store(output_ptr + offsets, output, mask=mask)

def triton_add(a: torch.Tensor, b: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

output = torch.empty_like(a)

n_elements = output.numel()

MAX_BLOCK_SIZE = 1024

grid = (triton.cdiv(n_elements, MAX_BLOCK_SIZE),)

add_kernel[grid](a, b, output, n_elements)

return output

size = 128

a = torch.randn(size, device='cuda')

b = torch.randn(size, device='cuda')

output = triton_add(a, b)

print("Triton output")

print(output)

In order to understand this, we need to understand memories and parallel programming. Since this lab is just a tiny experiment, we will not go deep into all the concepts but just explain what is happening here.

triton_add

n_elements = output.numel()calculates the total work to do based on the output size which is 128 in this case.- We set

BLOCK_SIZE, which defines the size of the data to process. gridcalculates how much pids are needed to execute the elements according to BLOCK_SIZE. (In this case it’s 128/128 so we only need a single program to execute vector addition) CPU then sends the instruction to GPU to proceed vector addition.- We will talk about why the block size is set to 128 specifically, later in some other post (!TODO: I will link that part to here!)

- cdiv is used to include the leftovers after dividing into BLOCK_SIZE. (eg. 130 dimentions / BLOCK_SIZE will result in 2 instead of 1)

add_kernel

@triton.jitis a special decorator that makes the function into machine language(or kernel) that can be run in GPU. This means unliketriton_addfunction, inadd_kernel, we are using GPU programming. jit is short for just-in-time, which means the code compiles just in time as it runs.- As you can see in the parameter, we use pointers for inputs and output (

x_ptr,y_ptr, andoutput_ptr). This is because we load data from the GPU RAM. pidor program ids are unique ids(eg. 0, 1, 2…) given to the GPU. Each program(kernel) checks its id.- each program uses its id(eg. 1) and calculate it with the amount of work it should proceed defined by BLOCK_SIZE. (eg. pid=1 should start from

1*128to2*128-1) - Each programs parallely proceeds the process(in this example, it would be vector addition).

- mask helps to check if the offsets do not exceed the actual data range.

- Now, we take inputs from their pointers and load data based on the offests and mask.

- The vector addition happens in the ALU in GPU.

- Then we save the result to the output_ptr in GPU RAM.

### Comparing Performance

first tried to naively check the performance with shell’s time command but figured out it was an inappropriate tool to check the actual performance between two codes.

time command measures multiple things in the environment such as Python interpreter starting time, loading libraries, CUDA context initializing (which takes a lot longer than the actual vector addition), and the GPU operation.

The more accurate way to check performance is to measure using torch.cuda.Event

I made a simple benchmark.py to measure the difference:

import torch

from add_triton import triton_add

def benchmark_pytorch(a,b):

return a + b

def run_benchmark(fn, *args):

start_event = torch.cuda.Event(enable_timing=True)

end_event = torch.cuda.Event(enable_timing=True)

# Warm-up for GPU

for _ in range(10):

fn(*args)

torch.cuda.synchronize()

start_event.record()

for _ in range(100):

fn(*args)

end_event.record()

torch.cuda.synchronize()

elapsed_time_ms = start_event.elapsed_time(end_event)

return elapsed_time_ms / 100

device = 'cuda' if torch.cuda.is_available() else 'cpu'

size = 1024 * 1024

a = torch.randn(size, device=device)

b = torch.randn(size, device=device)

pytorch_time = run_benchmark(benchmark_pytorch, a, b)

triton_time = run_benchmark(triton_add, a, b)

print(f"Vector size: {size}")

print(f"PyTorch average time: {pytorch_time:.6f} ms")

print(f"Triton average time: {triton_time:.6f} ms")

torch.cuda.synchronize() is used to force CPU to wait until GPU operation is done. Since the default behavior between CPU and GPU are asynchronous, we use this command to check the precise amount of time of the GPU operation.

I’ve tried with size = 128 but it was so short the noise took too much portion so I increased the size into 1024 * 1024.

❯ python benchmark.py

Vector size: 1048576

PyTorch average time: 0.124672 ms

Triton average time: 0.124037 ms

result was almost the same.

We can conclude that vector addition is so simple + PyTorch optimized it well that there seems no room for optimizing vector addition better than PyTorch. PyTorch is as good.

I guess we will have to cover things computationally heavier, such as matmul.

Note: Source code can be found in here

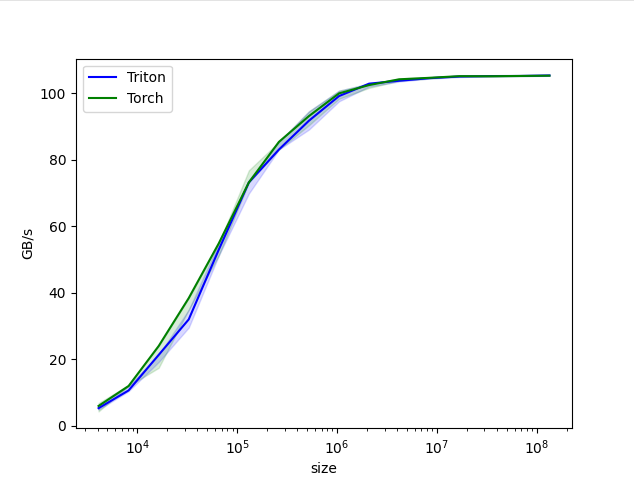

Note: Ran the actual tutorial code from Triton Tutorials and got the plot below: